Retaining refining capacity could pose long-term risks for South Africa

LAST MAN STANDING Sasol's Secunda refinery will likely be the last to close down, owing to the wide array of products that it supplies to the country

SYNFUELS SUPPLEMENT Sasol’s Secunda Synfuels Operation is the world’s only commercial coal-based synthetic fuels manufacturing facility

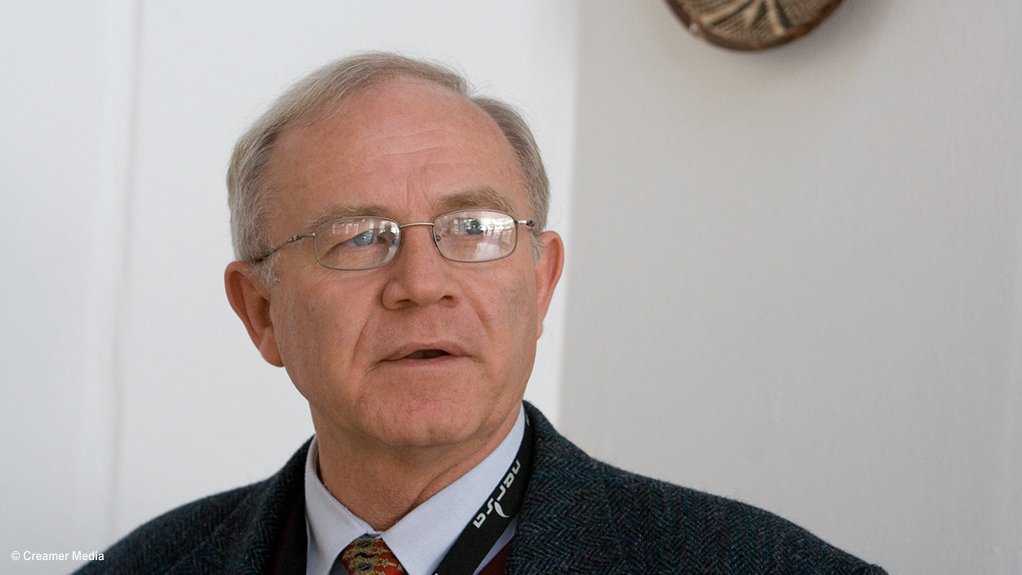

DAVE WRIGHT Buying the aged Sapref refinery is not necessarily the best option

Photo by Creamer Media

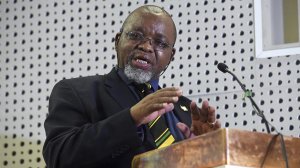

GWEDE MANTASHE The Mineral Resources and Energy Minister has spoken in favour of nationalising Sapref

South Africa’s oil refining capacity has always been rather small when considered on a global scale, but there was some sense of national pride and of security in knowing that the country could deliver – even if most of the crude input had to be imported.

While local refineries were never able to fulfil South Africa’s demand for fuel in recent times – at 25-billion litres a year – local refining capacity helped to supplement imported supplies.

However, it would seem that the country is heading inexorably towards becoming almost entirely dependent on imports, as the local crude refinery industry seems to be drying up.

Industry body the South African Petroleum Industry Association (Sapia) executive director Avhapfani Tshifularo explains that South Africa currently meets about 60% of its fuel demand through imports – a figure which many experts believe will continue to rise.

Over the past few years, the country’s refining capacity has steadily been dwindling as the ageing local refineries have stopped operations one after the other on the back of significant global and domestic shifts in policy, supply constraints, rising production costs and the increasingly unfavourable economics of fossil fuel dependence in a world headed for greener energy pastures.

The latest blow to the local refining industry was the mothballing of South Africa’s largest refinery at the end of March. Shell and BP South African Petroleum Refineries (Sapref), in KwaZulu-Natal, had a peak capacity of about 180000 bbl/d, or a contribution of 35% to the country’s crude refining capacity, which amounts to about 25% of South Africa’s total liquid fuels production capacity.

The decision to indefinitely pause operations and freeze spending at Sapref, made by co-owners BP Southern Africa and Shell Downstream South Africa, was taken to allow for an informed finalisation on the various options available – a sale option being the most preferred.

Although BP Southern Africa CEO Taelo Mojapelo said in February that contingencies had been put in place to ensurethe shutdown of the refinery did not impact on customer-facing businesses in South Africa or fuel supply obligations, politicians, analysts and industry players have been left wondering about the way forward.

Since Sapref’s halt was announced on February 10, talk of the State possibly acquiring the operation has been circulating, with KwaZulu-Natal Premier Sihle Zikalala and Mineral Resources and Energy Minister Gwede Mantashe both going on record with sentiments in favour of nationalising the refinery, most likely through the State-owned Central Energy Fund (CEF).

CEF corporate affairs manager Jacky Mashapu all but confirmed that talks were under way by telling Engineering News & Mining Weekly that the CEF was not able to comment owing to a nondisclosure agreement being in place.

Moreover, various news outlets reported that a CEF delegation was seen visiting the refinery in early March.

However, energy association the South African National Energy Association director Dave Wright does not believe that buying the aged refinery is necessarily the best option, which will cost taxpayers more than it is worth to keep operating and could leave the country with a stranded asset in about 10 to 15 years.

“Government is fixated with the idea that security of supply is linked to processing crude oil. That may have been the case several decades ago, but not anymore,” he tells Engineering News & Mining Weekly, noting that more than enough refining capacity exists globally to make up for the shortfall that would arise from local refineries’ closing.

Global refinery capacity in 2020 amounted to about 101.2-million barrels a day, while actual global refinery throughput was about 76-million barrels a day, thus leaving spare capacity of about 25-million barrels a day. This figure will likely increase as the developed world continues to move away from liquid fuels as part of the electric vehicle revolution, consequently reducing demand.

“There are going to be many refineries globally that are supplying products to a market that is shrinking. They’re going to be looking for new markets. If South Africa continues using liquid fuel products for a longer period than other parts of the world, then it will work out just fine,” Wright says.

He believes that the quantity of imported fuel required to replace that which was once produced locally is eminently doable.

To illustrate: at its peak in 2014, South Africa’s crude oil refinery capacity was about 508000 bbl/d of crude, with an additional 195000 bbl/d of synthetic fuel, totalling about 703000 bbl/d – about 0.6% of the total global refining capacity.

For comparison, the world’s most productive oil refiner – the US – can refine about 18.1-million barrels a day, followed by China, at more than 16-million barrels a day, and then Russia, at about 6.7-million barrels a day.

Although Russia’s role as a supplier might be in question during its ongoing invasion of Ukraine, Tshifularo believes that it will not remain a permanent feature of the global oil market and, therefore, should not factor into long-term decisions.

He explains that the shift away from local fuel production will not necessarily be more pricey in the medium to long term, since local production has always been subject to global oil price fluctuations, owing to South Africa’s having to import crude.

State of Local Refineries

Sapref was not the first local refinery to halt operations. Energy company Engen closed its 120000 bbl/d Enref refinery in Durban, in KwaZulu-Natal, in December 2020, following an explosion.

The company has since said the refinery will be repurposed into a fuel import terminal.

Online news outlet Fin24 reported in February that diversified miner Glencore’s 100000 bbl/d Astron Energy refinery in Milnerton, Cape Town, was scheduled to restart at an unspecified date later this year, after production stopped mid-2020 because of a fire.

Until Astron restarts, the only local crude oil refinery still in operation is the 108000 bbl/d Natref refinery in Sasolburg, in the Free State, which belongs to a joint venture between energy companies Sasol Oil and TotalEnergies South Africa.

Supporting Natref is Sasol’s Secunda Synfuels Operation, which comprises the world’s only commercial coal-based synthetic fuels manufacturing facility, producing synthesis gas through coal gasification and natural gas reforming. The Secunda plant has a capacity of about 150000 bbl/d crude equivalent.

“As long as Secunda is in operation, South Africa will not be wholly dependent on imports,” Wright says, adding that the refinery should be the last to close down, owing to the wide array of products that it supplies to the country – such as chemicals and fertiliser, among others.

The only other refining capability is State-owned PetroSA’s gas-to-liquids refinery in Mossel Bay, Western Cape, which was designed to process about 45000 bbl/d crude equivalent, but has been struggling to secure gas supply since 2020.

The refinery is, therefore, currently on care and maintenance. Nonetheless, Mantashe has publicly and adamantly declared that it will not be sold off, calling the dormant refinery a “a very important asset of the State”.

Job Losses

While South Africa’s fuel demand might be met through imports, Tshifularo remains concerned about the job losses that will occur as a result of refinery shutdowns.

At the end of August 2021, the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy gazetted new regulations regarding Petroleum Products Specifications and Standards; this has forced domestic refineries to decide whether they will be upgraded to meet these new regulations.

“Failure to upgrade will mean that tens of thousands of jobs will be placed at serious risk, as these refineries will be forced to close. This includes jobs not only at the refineries but also in the industries associated with the refineries – those that supply services to the plants and those that rely on the production of specialty products from these plants. Keeping refineries operational means securing these livelihoods,” Tshifularo implores.

The new regulations take effect on September 1, 2023.

“Sapia is of the view that the very short timeframe provided for implementation is impossible to meet and will likely render the refinery fleet obsolete within two years,” he said.

Wright notes, however, that if the State does buy Sapref, it will likely be forced to shift the deadline to a later date to accommodate itself, as any upgrades required will not be possible in the timeframe available.

Port Bottlenecks

While jobs might be lost in the refinery space, other jobs might be created in infrastructure development as South Africa’s port capacity will be forced to upgrade rapidly.

Wright is concerned that the ports will not be able to handle the extra volume of imported fuel, consequently causing a potential bottleneck that could throttle supply if not addressed urgently.

“It must be remembered that we will not import a single stream of crude through the Single Buoy Mooring, but rather multiple streams of different finished fuel products, which adds to the volume through the ports,” he explains.

South Africa’s ports are renowned for their inefficiency and for causing extensive delays. If left in their current state, without urgent and significant upgrades in terms of infrastructure and performance capabilities, there seems to be little doubt that they would not be able to handle the increased demand for imported fuel.

In May last year, Engineering News & Mining Weekly reported that the World Bank’s inaugural ‘Container Port Performance Index 2020’ ranked the Port of Cape Town among the worst in terms of container port performance.

The Port of Cape Town – South Africa’s best-ranked port – ranked lower than all the other ports in Africa, coming in at number 347 out of 351 ports reviewed.

South Africa’s other container ports, such as Gqeberha and Ngqura, in the Eastern Cape, as well as Durban, in KwaZulu-Natal, all dominated the lower end ofthe index.

“Our port capacity is where the true danger and risk lie. An increase in imported fuel requires infrastructure to be built in the ports to handle greater volumes. However, infrastructure development takes time. Not much can be done on a short term basis,” Wright concludes.