Houses of Parliament blaze highlights need for fire protection for heritage buildings

The fire that broke out at the Houses of Parliament in central Cape Town on 2 January has again raised the issue of protecting heritage structures and other buildings containing priceless artefacts or documents from fire risk. The fire is believed to have started on the third floor of the National Council of Provinces building before spreading to the office space and gymnasium and then the National Assembly building, which was completely gutted.

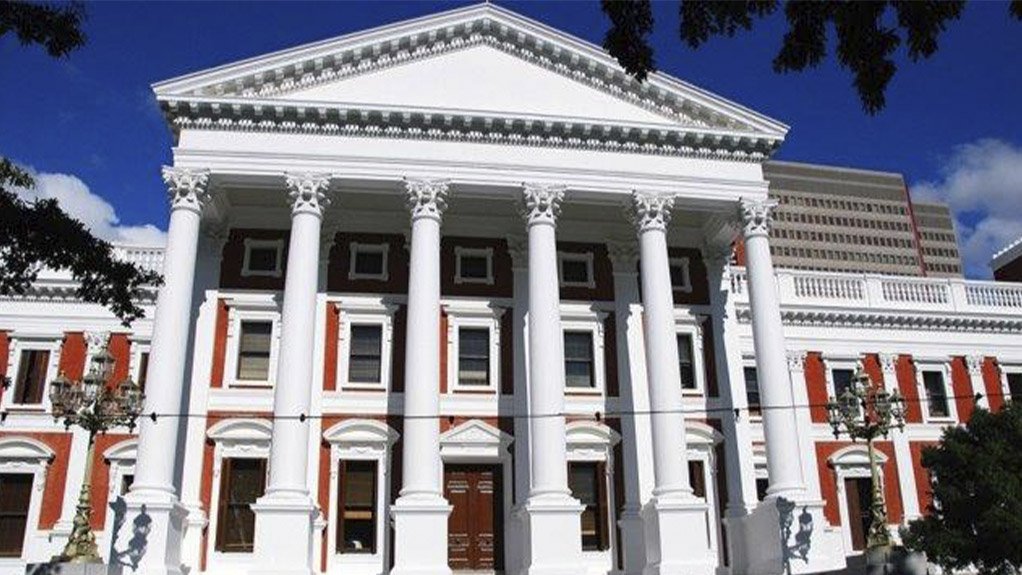

The Houses of Parliament consist of the original building, completed in 1884, and additions built in the 1920s and 1980s. These house the National Assembly, the lower house of the bicameral Parliament of South Africa, while the original building houses the National Council of Provinces, the upper house of Parliament.

The original parliament building was designed in a neoclassical style that incorporates elements of Cape Dutch architecture. The later additions were designed to blend in with the original building. The Houses of Parliament have received Grade 1 National Heritage Status by the South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA), its highest rating.

In mid-April last year, a fire originating at Table Mountain eventually swept onto the upper campus of the University of Cape Town (UCT). It caused extensive damage to the African Studies Library reading room, known previously as the JW Jagger Library. Built in the 1930s, it is home to many international research collections, with an estimated 85 000 items in total.

“It is particularly challenging where you have a building that did not necessarily have fire resistance measures incorporated into its design,” points out ASP Fire CEO Michael van Niekerk. A key consideration with a heritage building is if it has been adapted from its original function and construction, or is it a relatively new building that can accommodate such measures?

The construction materials used in older buildings are often not in line with modern regulations. Complicating the issue is that heritage buildings are difficult to retrofit with conventional sprinkler systems, for example, due to the fact that their external appearance has to be preserved.

Modern buildings also deploy drencher systems that can cool the exterior with water curtains to protect windows, doors, walls and roofs against an encroaching fire. “This is probably the best strategy to adopt in the event of a fire like the Table Mountain blaze, as it means a heat shield is essentially created around a building in order to protect it,” stresses van Niekerk.

In addition to modern advances like recessed sprinkler systems, which are only activated in the event of a fire, another solution is a hypoxic system that introduces nitrogen into an area to reduce the oxygen level to the point where spontaneous combustion cannot occur.

However, the best approach remains a proper fire-risk assessment that examines a building holistically. There are also internal factors that need to be considered, such as the possible sources of ignition inside a building and how best to manage these. Notwithstanding that a building is old, the electrical system can still be modernised without affecting its heritage ‘look and feel’.

In addition, modern electrical management systems based on earth leakage and thermal resistors, as well as computer monitoring, can result in an automatic shutdown if any risks are detected. These can range from fans, heaters and computer terminals that are left on to overloaded multi-plug extensions, a common cause of fire in a typical office environment, for example.

“Managing the internal environment of a building adequately allows for the fire risk to be minimised. Obviously, risk can never be eliminated by 100%, but it can definitely be reduced to an acceptable level,” highlights van Niekerk. An effective means to achieve this is to introduce refuge areas into heritage buildings in particular as part of the overall life-safety strategy. A refuge area has its own oxygen supply and fire-rated walls and doors to protect occupants until a fire dies down or is brought under control.

“There is an onus on the owners or trustees of a heritage or historic building to safeguard that building against fire. This is a risk assessment that any responsible building owner should conduct. It is advisable for any commercial or academic institution to request their insurers to come take a look at their buildings in order to give them advice. If the insurer does not have the necessary technical expertise or experience, ASP Fire offers this specialised service to a host of insurers,” concludes van Niekerk.