First electric minibus taxis to be piloted in Cape Town next year

By this time next year, it will be possible to tell whether electric minibus taxis are viable people movers within the South African transport landscape.

By then, newcomer to the domestic automotive landscape flx EV aims to have 40 battery electric taxis up and running in and around Cape Town, with Century City acting as the central hub and charging point.

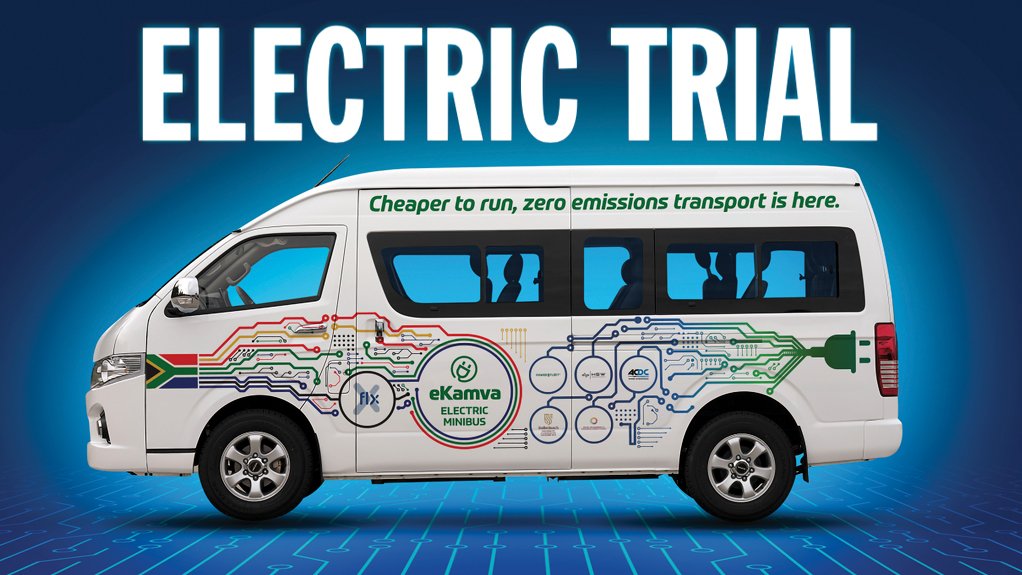

The taxi, the eKamva, will be imported from Chinese vehicle manufacturer Higer, Swedish truck maker Scania’s partner in the Asian country.

The eKamva is currently undergoing homologation in South Africa.

While flx EV may be a newcomer to the South African auto industry, the company’s CEO is not. The 39-year-old Justin Coetzee – a civil engineer by training – is also the man in charge at GoMetro.

In basic terms, GoMetro offers fleet management tools in what it calls Integration-Platform-as-a-Service (iPaaS) – which means it collates different data streams into something fleet managers can understand, use and act on.

The company is especially active in the heavy and public transport fields, here and in the UK.

Where It All Started

flx EV in 2023 received funding from the Department of Science, Technology and Innovation and its uYilo eMobility Programme to generate a blueprint for taxi-rank-adjacent electric vehicle (EV) charging.

The company designed such a charging facility for the Century City multipurpose node in Cape Town, next to the N1 north-bound, with the fenced-off charging facility to be located next to the taxi rank.

The facility will feature five chargers with two nozzles each that would be able to service ten vehicles simultaneously.

The overhead solar panel array will generate only sufficient energy to power the lights, and not the chargers, while also providing shade for the vehicles.

“We’ve done the modelling and you would need three soccer fields of solar panels to charge the vehicles, which is all but impossible in an urban environment,” notes Coetzee.

“The taxis will reverse into the facility in order to charge,” he adds. “We’ll be able to support six to ten vehicles, depending on the size of the initial installation.”

“The ten-nozzle, five-charger CCS2 installation will require a maximum of 600 kW of power.

“We can build another ten charging stacks and we’ll still only need a standard three-phase connection without extensive grid upgrades.

“Under this configuration, we don’t require a substation upgrade, and the grid upgrade to accommodate the charging facility will cost roughly R2-million.”

The chargers will all be DC chargers – fast chargers – which means they will be able to take the eKamva from a zero to 80% charge in 45 to 50 minutes.

“Behind the chargers, we’ll have the site controller, as well as space for battery storage at a later stage,” says Coetzee.

“As the taxi batteries end their mobility application in eight to ten years’ time, those batteries can potentially be used as storage systems alongside the charging units in a second-life application.”

Concept to Reality

“We are now in the phase where we are working with development funding institutions (DFIs) to pull together a consortium to put in the actual charging infrastructure,” says Coetzee.

“We have moved from concept to demonstrator implementation.”

According to Coetzee, the goal is to have the first taxis operating from the Century City hub by the middle of next year.

“We estimate that we need R40-million to R60-million to build the first hub and bring in the 40 taxis linked to this hub.

“We are talking to all the DFIs, the Public Investment Corporation, the Development Bank of Southern Africa and the Industrial Development Corporation – all those guys – to unlock the project.

“We then want to draw up a unit economics model that we can take to the big banks, climate funds and infrastructure funds to say that if one such hub is profitable, the same can be true for 300 hubs – built one by one – which we think is doable in ten years.

“So the next phase of the programme is to reach unit economics for a single hub on a reasonable number of vehicles,” says Coetzee.

“We need a bankable model and this is it. This is a demonstrator which should give us the profit-loss proof we need.”

Data is King

Before chargers and electric taxis, there was data.

GoMetro is the eKamva project’s data collector, as well as the project sponsor managing the charging software and telematics.

“We used data to model taxi operations in and around Century City before we started this process,” explains Coetzee.

“We saw that the taxis using this rank covered an average range of 256 km a day, with a maximum trip distance between rank visits of 90 km.

“The total time a taxi spends at the rank is around 2.5 hours a day, with the maximum uninterrupted time 1.5 hours.

“The taxi will go to Khayelitsha, for example, and back again – 70 km – and then park after that run for 30 minutes to 90 minutes, which gives the drivers enough time to charge in between all their runs.”

The range of the current eKamva is 200 km.

Coetzee says flx EV will generate a unique data set for each charging hub.

“We plan to take this process hub by hub – until you have 300 hubs and 24 000 electric taxis across South Africa.”

The Taxi, Reinvented

Within this hub project, the flx EV consortium – with its make-up still being finalised – will act as the importer, manufacturer and potential taxi builder, as well as the charging infrastructure developer.

flx EV is registered with the National Regulator for Compulsory Specifications as a manufacturer/importer/builder (MIB).

“About two years ago, I started to wonder why there was no electric taxi in South Africa,” says Coetzee.

“We struggled to find a 5.8-m-long taxi, like the ones we use in South Africa, with 9 m the typical size of a small bus in Europe, for example.

“Eventually we stumbled upon Higer, with the initial test bus arriving at the start of this year, when it underwent extensive testing.”

Buying a one-off concept vehicle especially built for the South African taxi environment has proved to be cost prohibitive in terms of early mainstream adoption, notes Coetzee.

“But the price will come down if we place an order for 40 units and have a pipeline for the future.

“Also, using the data, we can ask ourselves if we need a taxi with a 200 km range.

“Perhaps we might have a 100 km taxi, a 200 km taxi and a 250 km taxi – with the lower-range taxis coming in at a lower price, as the battery will be smaller.”

Another factor rendering the electric taxi expensive is a 25% electric vehicle import duty, as well as a 23.5% ad valorem duty, which means there is a combined 48.5% in duties being levied on each vehicle.

“If we take that off, we can almost sell the vehicle at the price of a diesel equivalent,” says Coetzee.

Higer has given flx EV naming rights for the vehicle, with the chosen name eKamva – isiXhosa for “into the future”.

“We are now putting the vehicle in front of the taxi industry and the many local taxi associations,” says Coetzee.

“We want their feedback on seating, the look, performance – everything.”

The eKamva is slightly higher than its standard competitors, with the floor also higher to accommodate the lithium phosphate batteries, made by the world’s largest battery manufacturer – CATL, based in China.

The batteries carry an eight-year warranty.

The batteries make the vehicle 500 kg heavier than competing internal combustion engine taxis, but seating remains the same – 13 seats in the back, plus the driver, plus two seats in the front.

“The motor is a 90 kW motor, with more torque than a diesel vehicle,” says Coetzee.

“We are also working on putting some smart tech inside, such as an AI camera that will monitor the driver for instances of distracted driving, harsh braking and so forth.

“Our technology will send a short video clip to the owner every time something like this happens.”

flx EV is also working with Visa and other suppliers to enable contactless payment, and/or payment by Whatsapp, via a Cape Town startup.

“We are also working on in-vehicle high-speed 5G WiFi – 270 megabits a second – with MTN as our partner,” says Coetzee.

He adds that flx EV is also considering wheelchair access, in reaction to a request from the Department of Transport.

“We are investigating whether we can replace the front seats with flip-up seats to accommodate a wheelchair.

Our biggest challenge is to then incorporate a pull-out ramp into the taxi floor.”

Coetzee says the eKamva will hopefully be registered on eNatis in November, which will kick off the selling process.

“Our concept is to sell taxis linked to each of the hubs we are developing. So our first orders will be for Century City.

“Owners will place orders with a deposit. Based on that, we’ll negotiate pricing and import the first units.”

Made in SA?

Eco-driven nonprofit GreenCape completed a cost comparison study between a diesel- equivalent minibus and the zero-emission eKamva.

“Basically, you can buy a diesel-equivalent vehicle for R700 000, or buy an EV for R1.2-million,” says Coetzee.

“That is almost double the capex, but the EV’s running cost will be R1.40, versus R2.50 for that of the diesel vehicle.

“Maintenance costs on the EV are also much lower. The diesel vehicle has 2 000 moving parts versus ten things that can go wrong on the eKamva.

“This means we need to convince taxi owners on the concept of total cost of ownership.”

Coetzee confirms that flx EV is mulling local semi-knockdown assembly, which should remove the 48% duty, “plus we may then also qualify for some benefits under government’s Automotive Production and Development Programme”.

“We are not doing this to continue importing.”

flx EV is currently considering Cape Town for local assembly, but Coetzee notes that the city is at an disadvantage, as the country’s automotive supply chain is located in Gauteng, the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal, despite the Western Cape’s dominance in the battery economy.

“With semi-knockdown assembly you need windscreens, linings and tyres, for example.”

“Rosslyn in Pretoria is an option, as are Durban and Springs.”

Coetzee says flx EV will consider semi- knockdown assembly once it has sufficient demand, at around 3 000 to 5 000 units a year.

Full assembly could become a possibility north of 10 000 units a year.

Coetzee highlights a current policy gap that could stall flx EV’s local assembly ambition, and that is the fact that government’s Electric Vehicles White Paper, published last year, speaks only to passenger vehicles and not commercial vehicles.

“We are working with government to reconsider this. Our project is very South African, so there is a lot of interest from government, and, we believe, huge demand from the rest of Africa.”

Coetzee adds that Higer’s staff has already visited South Africa, “and that they get it”.

“Next year we’ll go to their plant and see what is possible in terms of ensuring the eKamva meets the needs of the local industry.”

But What about Resale Value?

An old Toyota Hiace minibus taxi will almost always sell.

But what about an electric taxi with a battery operating at 80% efficiency by year nine or ten?

How will flx EV circumvent what has become a rather sticky problem in the EV market – the resale value of electric cars?

The chassis price on the eKamva is the same as the cost of a diesel-equivalent vehicle, says Coetzee.

“Then you have the battery at around R250 000 to R500 000, depending on the size, and around R400 000 in duties added on top of that.

“This gets you to R1.2-million to R1.4-milllion – the latter for the longer-range vehicle.

“The duties can be addressed with local assembly. In terms of the battery, there are a few options we are considering.

“We think the taxi owner can, for example, transfer the battery, separate from the chassis, into a lease with an agreed, guaranteed buyback period,” says Coetzee.

“The taxi owner will then pay a fixed monthly fee for the battery, on top of the vehicle loan repayment for the chassis, for a monthly instalment that will, cumulatively, still beat a diesel or petrol equivalent vehicle in terms of total cost of ownership.

“After eight years we buy the battery back, and the taxi owner can then choose to enter a new battery lease with us, or buy a battery from the second-hand market, or find another battery product.

We then take the battery and refurbish it, sell it on, or use it in stationary applications.”

Article Enquiry

Email Article

Save Article

Feedback

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here

Comments

Press Office

Announcements

What's On

Subscribe to improve your user experience...

Option 1 (equivalent of R125 a month):

Receive a weekly copy of Creamer Media's Engineering News & Mining Weekly magazine

(print copy for those in South Africa and e-magazine for those outside of South Africa)

Receive daily email newsletters

Access to full search results

Access archive of magazine back copies

Access to Projects in Progress

Access to ONE Research Report of your choice in PDF format

Option 2 (equivalent of R375 a month):

All benefits from Option 1

PLUS

Access to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa for ALL Research Reports, in PDF format, on various industrial and mining sectors

including Electricity; Water; Energy Transition; Hydrogen; Roads, Rail and Ports; Coal; Gold; Platinum; Battery Metals; etc.

Already a subscriber?

Forgotten your password?

Receive weekly copy of Creamer Media's Engineering News & Mining Weekly magazine (print copy for those in South Africa and e-magazine for those outside of South Africa)

➕

Recieve daily email newsletters

➕

Access to full search results

➕

Access archive of magazine back copies

➕

Access to Projects in Progress

➕

Access to ONE Research Report of your choice in PDF format

RESEARCH CHANNEL AFRICA

R4500 (equivalent of R375 a month)

SUBSCRIBEAll benefits from Option 1

➕

Access to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa for ALL Research Reports on various industrial and mining sectors, in PDF format, including on:

Electricity

➕

Water

➕

Energy Transition

➕

Hydrogen

➕

Roads, Rail and Ports

➕

Coal

➕

Gold

➕

Platinum

➕

Battery Metals

➕

etc.

Receive all benefits from Option 1 or Option 2 delivered to numerous people at your company

➕

Multiple User names and Passwords for simultaneous log-ins

➕

Intranet integration access to all in your organisation