Accelerating replacement generation rather than 75% EAF should be main Eskom performance measure

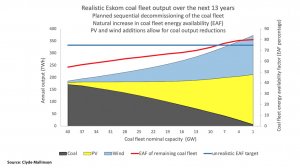

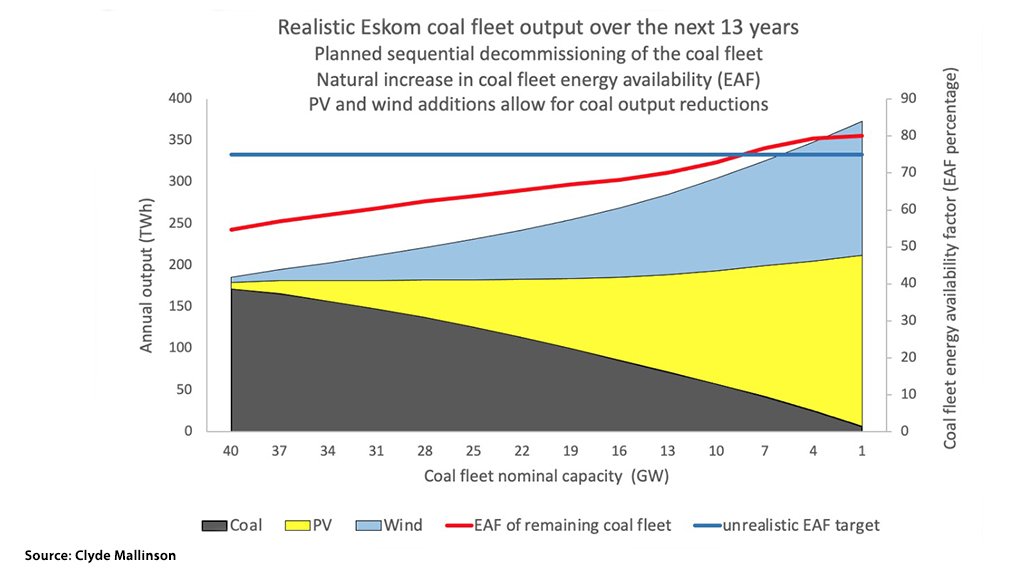

Mallinson’s model of what he sees as a realistic output from the Eskom coal fleet in the coming years

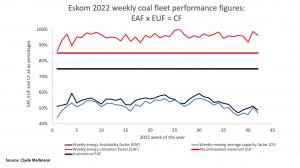

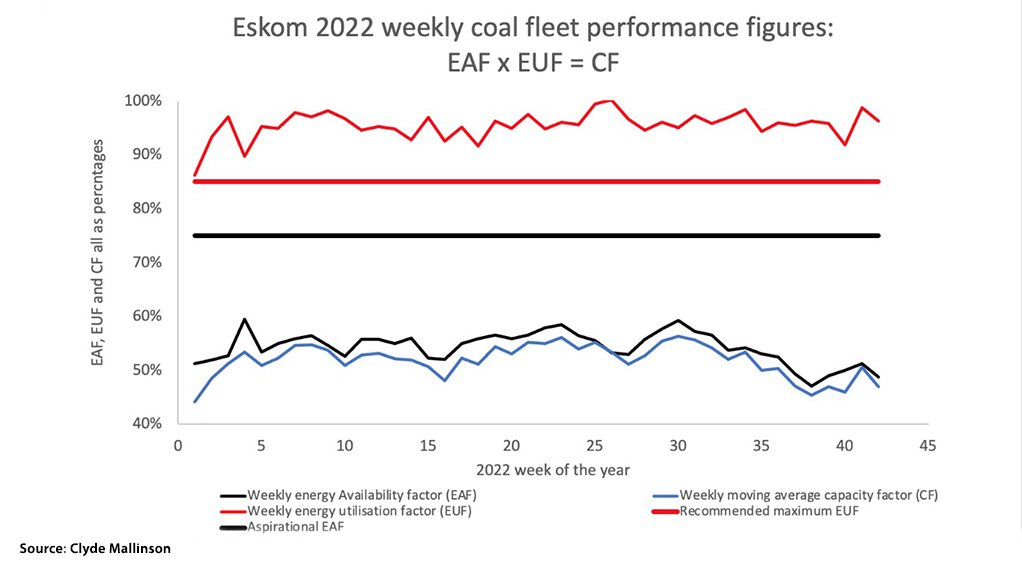

Eskom coal fleet performance in 2022

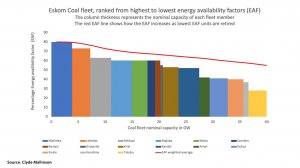

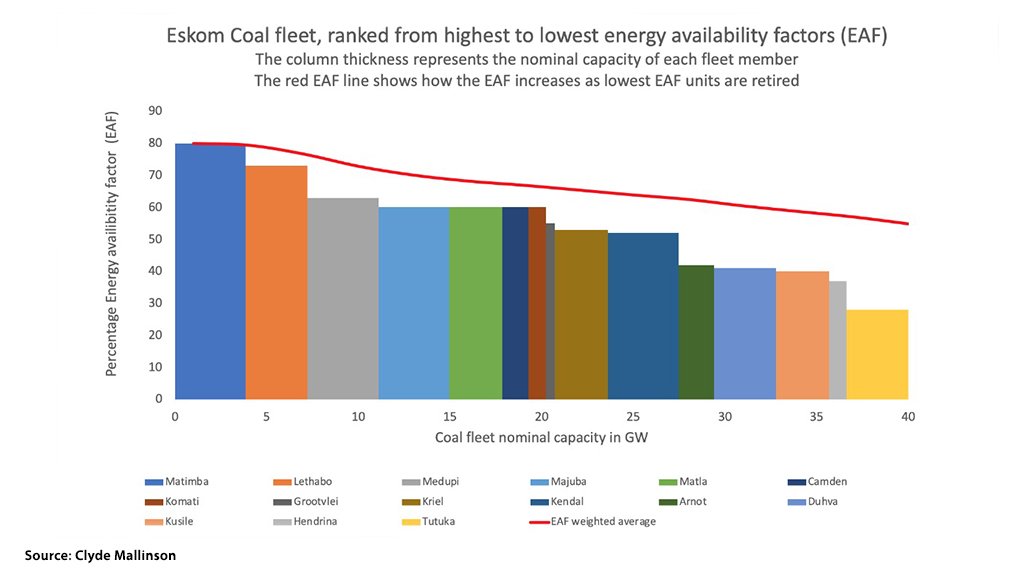

Eskom coal fleet EAF by power station

Setting a recovery in Eskom’s energy availability factor (EAF) to 75% as a key performance indicator (KPI) for the board and the executive is not only open to manipulation but is also the wrong measure in a context where the undermaintained coal fleet no longer offers the cheapest and quickest way out of loadshedding.

In fact, energy analyst Clyde Mallinson, who has done extensive modelling of the coal fleet’s performance using Eskom data, argues that sticking with this KPI will “set Eskom up for failure” and will stymie the transition to an electricity supply industry that is able to provide reliable and affordable power for all South Africans, rather than the current trajectory that points to price and supply “bifurcation”.

In other words, a scenario whereby pockets of consumers with access to power derived from solar and wind, with supportive storage, have access to electricity so competitively priced that it can be used to produce energy-intensive exports such as green hydrogen derivatives, while the majority remain beholden to a deteriorating coal fleet and continue to face steep price hikes and intensifying supply disruptions.

Mallinson stresses that the EAF measure is also only appropriate for the coal and nuclear fleets, as other technologies such as wind, solar, hydro, pumped storage, and gas or diesel generators have high availability factors but produce only when weather conditions are supportive, or if there is sufficient budget and/or infrastructure and logistics capacity available to burn gas or diesel.

He notes that the inclusion of non-coal technologies already offers a distorted picture of Eskom’s EAF, which is stated to be about 59% year-to-date, whereas it would be closer to 52% if only the coal EAF were to be disclosed.

In addition, the coal EAF is open to being manipulated, as is alleged to have occurred during the period of State capture at the utility, when coal units were kept running simply by ignoring warnings of mechanical distress, or by actively tampering with condition monitoring equipment.

The measure can also be managed upwards through removing units from the system, which changes the denominator, but does not increase output.

Having ranked the fleet from the highest to the lowest EAFs – with Matimba at 80% and relatively new Tutuka at below 30% – Mallinson is able to show that the EAF will improve as stations with the lowest EAF performance are retired. Some of these closures would lead to an only modest decrease in output as their remaining nominal capacity is low, but it could free up much-needed operator skills and spares.

However, the analysis suggests that recovering the EAF across all current operating units is unlikely, partly because of the poor state of the plant, where even non-wearing parts are failing, but largely because of the extreme energy utilisation factor (EUF) of the units when they are available, leaving little or no room for recovery maintenance.

The Eskom coal fleet EUF is currently well above 95%, which is out of kilter with global best practice of below 85%, so as to leave a 15% reserve margin.

As a result, the capacity factor of the coal fleet, which is the EAF multiplied by the EUF, is “dangerously” equivalent to the EAF, meaning that Eskom cannot rely on its coal stations to provide any reserve margin, and is even resorting to loadshedding to replenish its emergency diesel and pumped hydro reserves.

“The high EUF can be likened to a football team where every single player is carrying an injury, but they are being asked to play on, as there are no reserves and, thus, no time to allow players to have physio treatment.”

Therefore, in Mallinson’s view, the KPIs should be shifted away from EAF to having Eskom prioritise the urgent introduction of new replacement generation capacity, while making yearly commitments to specific, albeit declining, output levels from the coal fleet.

He has modelled what he believes to be a “realistic coal fleet output for the coming 13 years”, which indicates a fall in the fleet’s output, from about 175 TWh off a 40 GW capacity base to about 7 TWh off a 1 GW base. Over the period, the coal fleet’s EAF will recover from below 52% to 80%.

The energy gap left by the declining coal output will be covered primary through the building of solar photovoltaic (PV) and wind, backed by storage in the form of batteries and pumped hydro, and by the end of the period could be supplying 350 TWh yearly.

Such a scenario is increasingly reflected in Eskom’s own planning, including the recently released Transmission Development Plan, which points to the need for a significant acceleration in grid-related investments to facilitate the integration of 53 GW of new generation capacity, mostly renewables, over the next ten years.

In addition, the utility’s own plans do not factor in an EAF anywhere approximating the 75% reportedly embedded into the shareholder compact.

Even its optimistic recovery scenario points to an EAF of no higher than 69% by 2030 and cautions that the EAF could slump to between 59% and 61% for the remainder of the decade, equivalent to a coal fleet EAF of between 52% and 54%.

What’s more, Mallinson points out that apart from obvious risks associated with the planned life-extension of Koeberg, there are demonstrable economic reasons why it would not be prudent to seek to refurbish Koeberg during a period of known shortages in generation. There will be at least one additional level of loadshedding in South Africa for each day that Koeberg undergoes refurbishment.

Koeberg, he argues, can better serve known current supply shortages, and run through to the planned decommissioning date, thereby buying time to install replacement generation infrastructure.

Add to this the failure of Eskom to invest to meet the country’s legislated minimum emission standards (MES), that places 15 GW of coal capacity at risk immediately and 30 GW by 2025.

Eskom estimates that it will cost at least R300-billion to achieve full MES compliance and that such investments would take about 10 years to complete.

“Do you know how much wind and solar PV you can build for R300-billion?” Mallinson asks.

“The amount we need to spend on the new build is about $6-billion a year to add 3 GW of solar PV, 2 GW of wind and 1 GW of storage. So, we've got three free years of new build by not diverting R300-billion to the old coal plants and we can shut down 3 GW of coal yearly at the same time as we ramp up the other technologies.”

For this reason, Mallinson believes the shareholder’s main KPI for Eskom should be to build or facilitate the building of new replacement generation at an accelerated pace, so as to create headroom for any possible underperformance relative to the yearly output target set for the declining coal fleet.

“At the moment, we are dictating what the coal fleet should be able to produce rather than accepting what it can produce . . . [and] we are then setting aspirational targets as to what we think we would like the coal fleet to produce, and they're actually ‘pie in the sky’.

“The true aspiration should be all about the rate at which we can put in replacement generation, which then allows us, in an orderly fashion, to anticipate a contribution from coal that reduces every year.”

Article Enquiry

Email Article

Save Article

Feedback

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here

Comments

Announcements

What's On

Subscribe to improve your user experience...

Option 1 (equivalent of R125 a month):

Receive a weekly copy of Creamer Media's Engineering News & Mining Weekly magazine

(print copy for those in South Africa and e-magazine for those outside of South Africa)

Receive daily email newsletters

Access to full search results

Access archive of magazine back copies

Access to Projects in Progress

Access to ONE Research Report of your choice in PDF format

Option 2 (equivalent of R375 a month):

All benefits from Option 1

PLUS

Access to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa for ALL Research Reports, in PDF format, on various industrial and mining sectors

including Electricity; Water; Energy Transition; Hydrogen; Roads, Rail and Ports; Coal; Gold; Platinum; Battery Metals; etc.

Already a subscriber?

Forgotten your password?

Receive weekly copy of Creamer Media's Engineering News & Mining Weekly magazine (print copy for those in South Africa and e-magazine for those outside of South Africa)

➕

Recieve daily email newsletters

➕

Access to full search results

➕

Access archive of magazine back copies

➕

Access to Projects in Progress

➕

Access to ONE Research Report of your choice in PDF format

RESEARCH CHANNEL AFRICA

R4500 (equivalent of R375 a month)

SUBSCRIBEAll benefits from Option 1

➕

Access to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa for ALL Research Reports on various industrial and mining sectors, in PDF format, including on:

Electricity

➕

Water

➕

Energy Transition

➕

Hydrogen

➕

Roads, Rail and Ports

➕

Coal

➕

Gold

➕

Platinum

➕

Battery Metals

➕

etc.

Receive all benefits from Option 1 or Option 2 delivered to numerous people at your company

➕

Multiple User names and Passwords for simultaneous log-ins

➕

Intranet integration access to all in your organisation