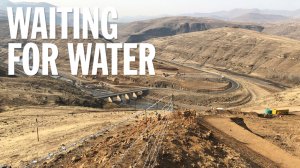

Delayed Lesotho Highlands project key to plugging Gauteng water-supply gap

The long-anticipated second phase of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP Phase II) broke ground this year, with ambitions of providing Gauteng and surrounds with a much-needed boost in water volumes by 2028.

The LHWP, a mutually beneficial, binational project between the Lesotho and South African governments, was established through a 1986 treaty and a 2011 agreement to leverage the water resources of the Lesotho highlands to provide hydropower to Lesotho and water to South Africa’s Gauteng province.

South Africa’s most populous province and economic hub has been struggling with unreliable water supply, with many regions, particularly high-lying areas, often going without water for hours, days or even weeks.

Many factors contribute to the shortages, including ageing and failing infrastructure, loadshedding, rapid urbanisation and significant volumes of nonrevenue water, besides others; however, the inflow of millions more litres of water daily is expected to go some way towards alleviating some of the challenges experienced.

Water utility Rand Water, with a total current supply capacity of 5 200-million litres of treated drinking water a day, has already exceeded its abstraction limits from the Integrated Vaal River System (IVRS), Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) director-general Dr Sean Phillips said during a Daily Maverick webinar titled ‘Reimagining Joburg: Weighing up the water crisis’, hosted on October 24.

The IVRS, the largest river system in South Africa, comprises 14 dams with catchments in four provinces, namely the Free State, the Northern Cape, Mpumalanga and the North West.

The DWS-issued licence allows the maximum abstraction of 1 347-million cubic litres a year from the IVRS, but Rand Water currently abstracts 1 680-million cubic litres, amid high peak demand and nonrevenue water, said Rand Water CEO Sipho Mosai.

Collectively, the City of Johannesburg (CoJ), the City of Tshwane (CoT) and the City of Ekurhuleni (CoE) are consuming 3 256- million litres a day as at October 30, up from 3 162-million litres a day as at October 23 and above the targeted 2 926-million litres a day, added Rand Water COO Mahlomola Mehlo during a weekly media briefing earlier this month.

Responding to a parliamentary question in September, Water and Sanitation Minister Senzo Mchunu said the CoJ has an allocated volume of 1 356-million litres a day, while the CoT and the CoE have allocations of 667-million and 1 022-million litres a day respectively.

“It would be irresponsible of the DWS to give us an additional abstraction allocation at this point in time until such time the LHWP Phase II comes on line and until such time our municipalities and ourselves deal with water-use efficiencies,” Mosai commented.

The DWS sets a limit on the amount of raw water Rand Water can abstract to ensure a continuous supply of water, particularly during droughts.

“One of our roles as the national department is to be very careful about the amount of water that is abstracted from raw water sources like the IVRS. While the dams might now be full, we do not know what is going to happen in a few months’ time.

“We cannot allow very high levels of abstraction, and then run the risk of the dams running completely dry, [leading to] a day-zero type of situation if there is a severe drought, which is quite possible as we know that the El Niño event has started again in South Africa,” Phillips explained.

While the DWS foresaw the increased demand from Gauteng, and planned the LHWP Phase II to augment the IVRS, delays in implementing the project meant that Gauteng will only start receiving the water in 2028 instead 2019, as initially planned.

The R40-billion Phase II project is expected to start water transfer in 2028, incrementally increasing the current water supply from 780-million cubic metres a year – sourced from the first phase of the project – to more than 1 027-million cubic metres a year by completion, with commissioning of the Oxbow hydropower scheme expected to follow in 2029.

The LHWP is the biggest infrastructure investment South Africa has participated in outside its borders, with the bulk of the capital required raised in South Africa’s financial markets by the State-owned Trans-Caledon Tunnel Authority (TCTA).

The TCTA is also responsible for the delivery tunnel transporting the water over the border to the Ash river, as well as all structures required to integrate and control the water flow in the river, while the Lesotho Highlands Development Authority (LHDA) manages the project portions within Lesotho’s borders, including the construction, operations and maintenance of all dams, tunnels, power stations and infrastructure, as well as secondary developments such as relocation, resettlement, compensation, supply of water to resettled villages, irrigation, fish hatcheries and tourism.

Although it was nine years behind schedule, the May 23, 2023, official start of the second phase of the multiphased project was a significant milestone – nearly 20 years after the inauguration of Phase I in 2004 after it was completed in 2003 – with the sod-turning marking the start of the construction of the water transfer main works, namely the Polihali dam and transfer tunnel, as well as the Senqu bridge above the Senqu river.

In November last year, the LHDA awarded the LHWP Phase II’s biggest contracts at the time for the construction of the Polihali dam and Polihali transfer tunnel.

The Polihali dam, a 165-m-high concrete- faced rockfill dam, will create a reservoir on the Senqu and Khubelu rivers with a surface area of 5 053 ha and a water storage capacity of 2 200-million cubic metres. The infrastructure includes a spillway, a compensation outlet structure and a mini-hydropower station.

The new dam is larger than the 145-m-high Mohale dam, which was constructed in Phase I of the LHWP, with capacity to hold 950-million cubic metres of water at its full supply level.

The planned 38-km-long Polihali gravity- led water transfer tunnel will connect the Polihali dam with the existing Katse reservoir, with water then transferred through the delivery tunnel to the ‘Muela hydropower station that was constructed in Phase I, and then on to the Ash river outfall outside Clarens, in the Free State, on its way to Gauteng. LHWP Phase II will further include the construction of a pumped-storage scheme, the associated transmission lines and appurtenant works.

The project includes the construction of new substations – one at the Polihali dam and another adjacent to the existing Matsoku diversion substation – the upgrading of existing Lesotho Electricity Company substations, the construction of new power lines and the diversion of some of the existing distribution network.

The construction of the advance infrastructure includes a network of roads, bridges, bulk power and telecommunications infrastructure and housing, said LHDA CEO Tente Tente.

In November 2023, the LHDA released a tender for the design and supervision of the feeder roads and bridges programme to upgrade existing and build new community roads and bridges surrounding and across the new Polihali reservoir that will be formed by the Polihali dam that is currently under construction in the Maluti mountains of Lesotho.

The overall programme will provide 94.2 km of access roads, four pedestrian bridges and six vehicle bridges, split into about eight different construction contracts, which will enable mobility and connectivity between communities that will be separated by the Polihali reservoir.

In August, the LHDA completed the construction procurement for the remaining two major bridges to be built under Phase II, and work started on August 29, with the two bridges across the Mabunyaneng and Khubelu rivers expected to be completed by October 2025.

The construction contract for the biggest of the trio of bridges – the Senqu bridge – was awarded in late 2022.

The LHDA also awarded the contract for the construction of the Polihali Commercial Centre in mid-January 2023, with construction expected to be completed by end of next year, along with the bulk of the Phase II advance infrastructure.

Work on the other construction contracts for the Polihali Village, upgrades to the Katse Lodge and Katse Village and the Polihali Operations Centre is progressing well, LHDA Phase II divisional manager Ntsoli Maiketso said at the time.

In August, the LHDA, consultants and contractors on the Polihali dam marked an early construction milestone – the diversion of the Senqu river into and through the diversion tunnels – ahead of the construction of the cofferdam upstream of the Polihali dam wall.

The Senqu river was diverted for the first time through a 9-m-diameter, 960-m-long diversion tunnel, one of the twin diversion tunnels constructed between 2019 and 2021 to divert the rivers’ natural flow and create a dry area, which will enable the construction of the permanent cofferdam upstream of the Polihali dam.

Without this diversion, no other elements of dam construction can take place, said Tente.

“It is indicative that Phase II, just a couple of months after being officially opened by our principals, is indeed now going full steam ahead. Our consultants and contractors have hit the ground running and we are all excited for what this means for the project, and for Lesotho and South Africa,” he said.

While Gauteng will have to wait another five years to source additional water, Rand Water, in preparation for the additional inflow, is undertaking a R35-billion capital programme to ensure that, by the time that additional water comes into the IVRS in 2028, the water utility will have additional capacity ready to treat a lot more water and provide it to the municipalities.

This includes the Station 5A filtration plant, at the Zuikerbotch water treatment works, outside Vereeniging, in the Vaal, which was completed in August, augmenting, in the first phase, the capacity of the plant by 150-million litres a day.

The Station 5 plant is divided into two phases, 5A and 5B, and the completion of Phase 2 Station 5B at the end of 2024 will add another 450-million litres a day, bringing the total to 600-million litres a day of water to the users.

While the LHWP Phase II will boost Gauteng’s water supply and will help to alleviate some of the supply challenges, there is still a need to be mindful that Gauteng is a water-scarce area in a water-scarce country, said Phillips.

The provinces’ long-term water consumption will need to be carefully managed, as there are limits to which further phases of the project or other water-transfer projects can continue to provide additional water to Gauteng at an affordable cost.

In the interim, the DWS is meeting continuously with municipalities and Rand Water and is supporting the municipalities to reduce the leaks within their systems and undertake infrastructure work to make them more resilient to breakdowns, amid a tight supply and demand environment.

Rand Water’s infrastructure is well maintained, he said, noting that the utility loses 3% of its water, owing to leaks, while many of Gauteng’s municipalities on average lose 25% of the water bought from Rand Water through leaks.

Article Enquiry

Email Article

Save Article

Feedback

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here

Comments

Press Office

Announcements

What's On

Subscribe to improve your user experience...

Option 1 (equivalent of R125 a month):

Receive a weekly copy of Creamer Media's Engineering News & Mining Weekly magazine

(print copy for those in South Africa and e-magazine for those outside of South Africa)

Receive daily email newsletters

Access to full search results

Access archive of magazine back copies

Access to Projects in Progress

Access to ONE Research Report of your choice in PDF format

Option 2 (equivalent of R375 a month):

All benefits from Option 1

PLUS

Access to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa for ALL Research Reports, in PDF format, on various industrial and mining sectors

including Electricity; Water; Energy Transition; Hydrogen; Roads, Rail and Ports; Coal; Gold; Platinum; Battery Metals; etc.

Already a subscriber?

Forgotten your password?

Receive weekly copy of Creamer Media's Engineering News & Mining Weekly magazine (print copy for those in South Africa and e-magazine for those outside of South Africa)

➕

Recieve daily email newsletters

➕

Access to full search results

➕

Access archive of magazine back copies

➕

Access to Projects in Progress

➕

Access to ONE Research Report of your choice in PDF format

RESEARCH CHANNEL AFRICA

R4500 (equivalent of R375 a month)

SUBSCRIBEAll benefits from Option 1

➕

Access to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa for ALL Research Reports on various industrial and mining sectors, in PDF format, including on:

Electricity

➕

Water

➕

Energy Transition

➕

Hydrogen

➕

Roads, Rail and Ports

➕

Coal

➕

Gold

➕

Platinum

➕

Battery Metals

➕

etc.

Receive all benefits from Option 1 or Option 2 delivered to numerous people at your company

➕

Multiple User names and Passwords for simultaneous log-ins

➕

Intranet integration access to all in your organisation