South Africa’s low-cost, high-value rare earths heading for global market entry

Rainbow Rare Earths senior metallurgist Roux Wildenboer interviewed by Mining Weekly's Martin Creamer. Video: Creamer Media's Shadwyn Dickinson.

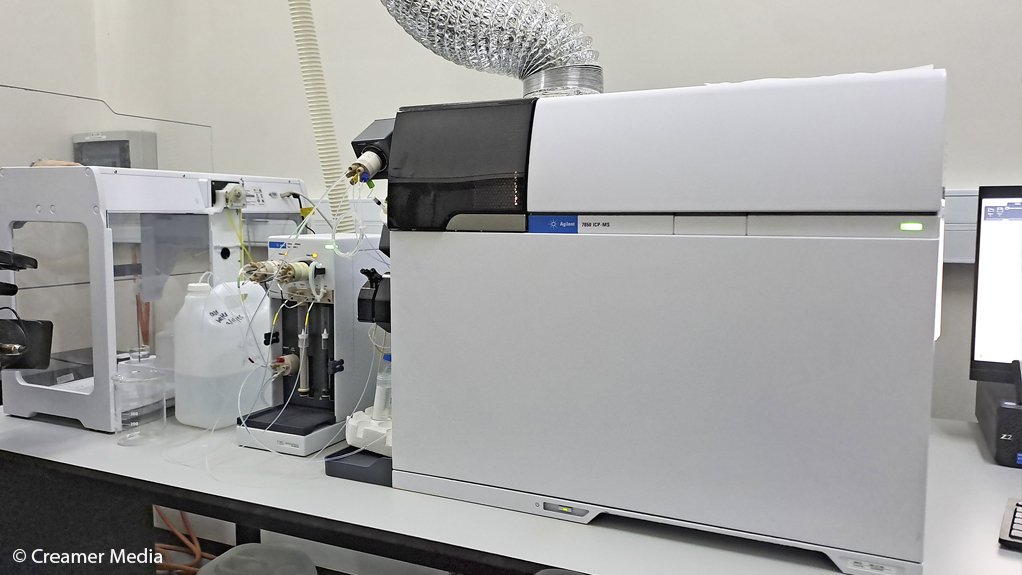

Rainbow Rare Earths laboratory in Randburg.

Photo by Creamer Media Chief Photographer Donna Slater

Rainbow Rare Earths laboratory in Randburg.

Photo by Creamer Media Chief Photographer Donna Slater

Rainbow Rare Earths laboratory in Randburg.

Photo by Creamer Media Chief Photographer Donna Slater

Rainbow Rare Earths senior metallurgist Roux Wildenboer.

Photo by Creamer Media Chief Photographer Donna Slater

JOHANNESBURG (miningweekly.com) – Mining Weekly has just visited the laboratories that Rainbow Rare Earths has established very innovatively on the north-western fringe of Greater Johannesburg as part of its journey towards completing a definitive feasibility study (DFS) that should see a wide range of South African rare earths enter the market to help to satisfy soaring global demand.

Remarkably, all the rare earths are being sourced from material on a waste dump in Phalaborwa, Limpopo, which is giving South Africa a significantly low-cost high-value lead-in to the commercial production of rare earths needed by the booming permanent magnet market.

Rainbow Rare Earths senior metallurgist Roux Wildenboer, who took the Mining Weekly team around the laboratories, ended the tour by displaying a handful of what he described as “good, final, high-quality product. We’re almost at the finish line. It's home stretch for us now. So, exciting times ahead.” (Also watch attached Creamer Media video.)

That is the extent of advanced development that the London-listed Rainbow has reached, in an effort that positions South Africa superbly to take full advantage of becoming a highly competitive supplier of these green economy commodities.

Historically, there was a massive quantity of phosphogypsum generated as waste from phosacid production of the State-owned Foskor in Phalaborwa.

Now, 35-million tons of it will enable 17 years of production of separated rare earth oxides for direct sale into end-use manufacture.

Rainbow is leasing laboratory premises from the State-owned Mintek, in Randburg, where Mining Weekly witnessed advanced process development, reagent consumption optimisation, a flow sheet that is close to final form, and most noteworthy of all, a pilot plant.

As final design parameters are precisely identified, the pilot plant is opening the way for scale-up and categorical proof that the process of taking the feed material downstream for on-site refinement works well.

The idea is to have a steady stream of high-value rare earths being produced at low enough volume for even a DHL overnight express service to deliver it to those in urgent need.

Rainbow is working towards publishing a DFS in 2026 and then going into full-scale construction as fast as it can thereafter.

It is important to point out that the Phalaborwa rare earths project has none of the traditional costs associated with blasting, crushing, milling, and flotation that production from typical hard rock phosphate rare earth ore requires elsewhere in the world.

Rainbow has the major advantage of being able to use already cracked rare earth host feed material on surface that gives it a headstart over everyone else, and the large quantity and highly concentrated material is readily leachable. Being above ground, the resource also lends itself to drone over-flights, density measurement, and being able to arrive at an accurate calculation of how much rare earth is available.

LABORATORY TOUR

In one section of the pilot plant, Mining Weekly was shown how material from site was making contact with a sulphuric acid solution, ahead of being leached in one of several heated and agitated tank reactors, all of which are South African manufactured by Afromix of Boksburg. In that process, the rare earths are extractable and kept in a leach solution in another section of the pilot plant.

The continuous ion exchange (CIX) unit shown to us had 30 columns, each containing small resin beads that help to extract the rare earths from the leach solution. The CIX is also a locally manufactured contribution from South Africa's IXT.

In passing the leach solution through the CIX, the resin adsorbs the rare earths, but not the other impurities. During the CIX process, the rare earths concentration is increased tenfold, so if two grams a liter in the solution go into the CIX, 20 grams come out of it.

This is the way that the full-scale plant is going to look and operate, only bigger, with all of the correct quantities of solutions, feed rates and sampling.

Overall, the multi-pump system recovers the rare earths, rejects most of the other impurities, and upgrades the rare earths so that whatever is done beyond the CIX process is considerably smaller.

The leaching circuit takes 300 t of gypsum an hour and the final product reaction tank has a capacity of 7.5 litres, which is the scale-down Rainbow is expecting on the full-scale plant as well.

Each column of the CIX gets a turn to go into every position as part of a fully automated process.

The filters, the tanks, and the drying ovens that can go up 2 200 o C are all locally made. Some of the pilot equipment has been taking quite a beating in the small-scale testwork that has been done and the local suppliers have been brilliantly on hand to service, refurbish, and repair.

The white, wettish phosphogypsum brought in from site contains about 0.4% rare earths and the laboratory has access to about 28 t of it, which is kept in a storage facility up the road.

Mining Weekly: So, for years and years, they've just put waste material on the Phalaborwa dump, and it's been lying there for decades. Then along came Rainbow Rare Earths, takes a look at it and discovers that it contains many rare earths. Tell us about that.

Wildenboer: Rare earths are a group of elements on the periodic table, usually those last two lines on the periodic table, that chemistry students cut off when they have to paste it in their books. They are elements with names that are difficult to pronounce and they are not often heard of. Two of the main ones that we’ll be turning into pure rare earth oxides are neodymium and praseodymium. Those two elements are considered light rare earth elements, and they go primarily into the manufacture of permanent magnets, which are basically what is driving the green technology revolution. They’re driving the production of electric vehicles, of wind turbines for power generation; your telephone vibrating motor probably has some permanent rare earth magnets in it, and if you walk into any kind of hardware store, you’ll see the neodymium iron boron, or NdFeB, permanent magnets hanging from a shelf. They’re used in a wide variety of applications and those are two of the most important ones that we're looking at. We're also looking at all of the heavy rare earth elements, of which there are about 16. Dysprosium and terbium are two of the target ones that we'll be producing as well in the form of a heavy, rich, mixed rare earth oxide or carbonate, at the end of the final refining stage. The aim of that will be to go forward into separation of these elements as individual oxides. The majority of rare earths in the Phalaborwa orebody are lanthanum and cerium, and although our aim would be to separate these two elements from the rest of the more valuable ones, there certainly is a market for lanthanum and cerium, if they can be sufficiently purified. The rest of the heavy rare earth elements include samarium, europium, gadolinium. Interestingly, gadolinium is injected into magnetic resonance imaging MRI patients to increase the contrast under a magnetic field of organs and bones. At the moment, rare-earth elements are driving a lot of the modern technology markets in that they are used for lasers, optics, the Internet, fibre cables, and radar imaging. By and large, the two most economically important to us, and probably for any rare earths project at the moment, are neodymium and praseodymium, and we are endowed with a comparatively high fraction of that in our Phalaborwa ore, with neodymium and praseodymium making up close to 30% of our rare earths basket, which is significantly higher than most typical rare earths projects and mines, and which positions the company in a very good space to supply these critical rare-earth elements.

GYPSUM RECLAMATION

In recovering rare earths from the stacks, Rainbow will also rehabilitate the environment. The aim is to reclaim the gypsum.

A modern, regulatory compliant line stack will be targeted and then systematically isolated gypsum can be used in the construction, food, mining and agriculture industries.

While gypsum is not a fertiliser as such, it can be and is mixed into soil to provide phosphates and sulphates to plants.

Already, a fraction of that gypsum is going into the local agricultural sector and Rainbow will be looking to sell off all the gypsum.

The process design is to treat 2.2-million tons of gypsum a year and Rainbow has been continuously updating the 35-million-ton resource as new assays and new modelling come to light.

Rehabilitation will theoretically begin from year one and the hope is that all the gypsum will be sold off over the 17-year period.

Mining Weekly: The price of one of the rare earths recently shot up by 3 000%. Why did it soar so high?

Wildenboer: The rare earth in question is yttrium - a rare-earth element that is always included in the rare earths basket. But the chemical molar masses of rare earths are always classified as the total rare earth elements, or total rare earth oxides, plus yttrium. Yttrium is considered as one of the rare-earth elements, but it is slightly different and only recently did the yttrium price rocket, primarily because of its use in modern technology. Luckily, we have a substantial chunk of our total rare earths basket that comprises yttrium. It is possible to separate, isolate and purify yttrium during our downstream refining step, and that's what we aim to do to tap as much value as we can out of that one specific element.

It seems like the Phalaborwa project is a gift that keeps on giving.

The reason why many, as we call them, igneous or hard rock phosphate-type rare-earth deposits are so expensive to exploit, is because the mineral is what they call very refractory to normal atmospheric and ambient temperature, so one of the first steps after crushing, milling and flotation is to crack this rare-earth mineral and that typically requires incredible quantities of reagents and energy. You can do that in one of several ways, but you always need either a lot of acid or a lot of an alkali called caustic sodium hydroxide. Our process comes into the picture way after that and the fact that other parties have been operating that phosacid plant for so many decades has actually cracked the Phalaborwa rare earths ore that they actually dug out of the ground to get to the phosphate. They've already cracked those rare earth minerals for us, so the rare earths are in the stacks in a form that is readily leachable, in conditions that are not as extreme as found in normal rare earths processes. The fact that the resource is above ground increases the confidence that we have in our resource estimates. With normal mining projects, you have to go and drill holes, and there's also that little section that you maybe have not drilled completely or that you miss and that's why often you see with gold and other commodities, the life-of-mine is extended as they move into orebodies that previously were maybe not explored thoroughly enough, or whatever, but there's always a measure of uncertainty. With us, we fly a drone over the stacks. We do density measurements, we survey the volume of those stacks, and we have a very, very high confidence about exactly how much rare earth and how much material there is. It's a big derisking thing that all of the material is on surface. It's easily reclaimable so you don't have to go in with massive tippers and haul trucks. Much smaller equipment can be used that is less hazardous to the people working there, so big, big plus factors on all fronts.

Where is new waste material currently being dumped?

Foskor is still running its flotation plant at Phalabora and Palabora Mining Company is also still continuing its copper mining operation. But currently, the Foskor flotation plant sends all of its phosrock concentrate to Richards Bay and the phosphoric acid plant in Richards Bay services the phosacid needs of the region and also exports.

When in 2026 will your definitive feasibility study be completed?

The completion of our DFS depends mainly on a couple of optimisation exercises that we’re still working on. We’re going to depend on data from this pilot plant to drive a lot of those final design decisions. But hopefully by the middle of 2026, we should have technical confidence in the flow sheet, and then it depends on how fast the engineering and the costing can be done. We're doing some optimisation trade-offs about where to source reagents and how material is brought to site and whether we should build plants on site to make our own reagents or whether we should buy or truck in reagents from an existing supplier. We're looking at energy balances and pond and water tank sizes. But, by and large, we have a very high level of confidence in the process and in the flow sheet. We wouldn't have gone into piloting had we not, at bench scale, done so much to verify this process. We've been working very hard on small bench-scale, lab-type operations. I'm talking maybe five-kilogramme leaches, which already, if you're talking in the sense of academic research, that's massive. If you tell any kind of university professor or student you're doing 5 kg leaches, their eyes will pop out because usually it's 50 g to 100 g. The feed material into this type of research is very scarce, but we've got 35-million tons of it, so we've been doing these kinds of lab optimisations, and that's guided the design and the construction of the pilot plant. The results from the pilot plant will guide design and trade-offs and during the course of 2026, we will have a DFS. Unfortunately, I can't give you any more certain guidance, other than it will be done before the end of 2026.

When will the pilot get onto that site and get built. Will that also be next year?

The pilot plant we're actually constructing in our facility in Randburg is going to be running for several months here. Then, once we do get going on site, we’ll transport the pilot to site and continue running it as a continuous optimisation and improvement tool. The pilot is a very nice little chemistry play set that will continue to run throughout the course of the 17 years of operation to provide side-stream optimisation – and who knows what could come out of that. In the meantime, the pilot will do its job leading up to the conclusion of the DFS and then we'll pack it up, send it to site, and restart it there. That will be as we begin large scale civils, earthworks and putting up the big tanks.

What will your rare-earth products look like and how will you get them to market?

The ongoing joke is that Rainbow takes in white powder, intermediate products are white powders, and at the end of the day, we produce something that is very high value but is also still a white powder. Our final product will look something like a white powder, but it will be very pure, and it will probably be able to go directly into magnet manufacture and downstream processing. The aim of the game for us is to set up the processing plant as well as the downstream refining process on site. We aim to do all of the refining and production of the end-product ourselves. At the end of the day, if we produce a mixed neodymium/praseodymium oxide, instead of white powder, it's a brownish, greyish powder, but so are the rest of the rare earths as well. If you look at any kind of rare-earth carbonate, it presents as some kind of white substance, much lower in volume than the circa 300 t/h of gypsum that we're going to be producing. From the final process, we aim to be producing a lot lower quantity of mixed neodymium/praseodymium oxide but far higher in value. It is easy to transport. Whoever the final offtaker or purchaser of the product that we produce will be, we’ll probably fly it to them or ship it to them. It's low enough quantities for, I would say, DHL overnight express, for someone who wants it urgently, but the idea is to have a steady stream of low-volume, high-value product coming out of that plant.

Is there no South African demand, is no one making permanent magnets locally?

Not currently, unfortunately. I wish that were the case. I think we certainly have the skill and know-how in South Africa to construct plants and capacity for this, but again, I think the whole of the Western world is struggling from restricted supply. Even if there was the intention in South Africa to start building magnets, we would be sitting with the same problem as the whole of the rest of the Western world. Currently, the supply of rare-earth materials is so limited, and that's why I think more of these rare-earth projects need to be brought online. There are certainly a lot of projects in the pipeline, many of them at various stages, some of them still at scoping level or preliminary economic assessment level. Some of them have completed DFS-level studies and are now, I believe, looking for funding. But I think in terms of us producing basically the final product, there’s not much market in South Africa to sell that into currently. We will be hoping to sell our residue gypsum into the South African market. But at the moment, the major demand for the rare-earth products that we will be producing is in the US and in Europe.

Is there a project in the world that's similar to this, where you've got material on surface and rare earths are being recovered from a pile of material on surface?

Currently, no. There's been a lot of academic research on the topic but, by and large, the academic research that's been done typically leaches phosphogypsum waste residue, but in conditions that we don't believe are economically feasible. In terms of people in the world that have come the closest to executing a project like this, there's nobody that’s as far advanced as we are. We have been approached by several other phosacid producers with the hopes of doing a project similar to Phalaborwa at their facility. One which we've been very excited to partner with is Mosaic in Brazil. We've been developing their Uberaba project in Minas Gerais during the course of the last several years. We are now hoping to be publishing a preliminary economic assessment on that project fairly soon and then we are also in talks with various other phosacid operators around the world. There is certainly interest in this type of technology because phosacid production is widespread. Almost every country in the world uses phosacid, which goes into fertiliser and beverage industries. We've been speaking to those still in the study phase of developing phosacid projects, as well as those with operating phosacid plants that now have gypsum residues that they'd like us to look at. So, yes, there are definitely other places where this technology can be implemented but none is close to us at the moment when it comes to know-how.

Article Enquiry

Email Article

Save Article

Feedback

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here

Press Office

Announcements

What's On

Subscribe to improve your user experience...

Option 1 (equivalent of R125 a month):

Receive a weekly copy of Creamer Media's Engineering News & Mining Weekly magazine

(print copy for those in South Africa and e-magazine for those outside of South Africa)

Receive daily email newsletters

Access to full search results

Access archive of magazine back copies

Access to Projects in Progress

Access to ONE Research Report of your choice in PDF format

Option 2 (equivalent of R375 a month):

All benefits from Option 1

PLUS

Access to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa for ALL Research Reports, in PDF format, on various industrial and mining sectors

including Electricity; Water; Energy Transition; Hydrogen; Roads, Rail and Ports; Coal; Gold; Platinum; Battery Metals; etc.

Already a subscriber?

Forgotten your password?

Receive weekly copy of Creamer Media's Engineering News & Mining Weekly magazine (print copy for those in South Africa and e-magazine for those outside of South Africa)

➕

Recieve daily email newsletters

➕

Access to full search results

➕

Access archive of magazine back copies

➕

Access to Projects in Progress

➕

Access to ONE Research Report of your choice in PDF format

RESEARCH CHANNEL AFRICA

R4500 (equivalent of R375 a month)

SUBSCRIBEAll benefits from Option 1

➕

Access to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa for ALL Research Reports on various industrial and mining sectors, in PDF format, including on:

Electricity

➕

Water

➕

Energy Transition

➕

Hydrogen

➕

Roads, Rail and Ports

➕

Coal

➕

Gold

➕

Platinum

➕

Battery Metals

➕

etc.

Receive all benefits from Option 1 or Option 2 delivered to numerous people at your company

➕

Multiple User names and Passwords for simultaneous log-ins

➕

Intranet integration access to all in your organisation